Differentiating your filter

I wanted to write up a really cool derivative filter that I got to implement on the 2019 year car. Since I’m responsible for torque vectoring with the car’s wheel hub motors (Shameless plug for future post), I’m doing a lot of sensor work. So far though, this is been the coolest project.

There is a straightforward approach to take the derivative of a discrete signal. If you skip the subtlety of how derivatives analogize to a discrete signals, you could just say something like $ \frac{d}{dt} x[i] = \frac{x[i]-x[i-1]}{\Delta t} $ . For a pure signal this actually works great. It has minimal phase lag, is causal (real-time), and only requires keeping track of the two most recent values in the signal. If you’re clever you can sample at a constant frequency which removes the time dependence and makes it an LTI system. Slightly more sophisticated techniques like the five-point stencil method work similarly.

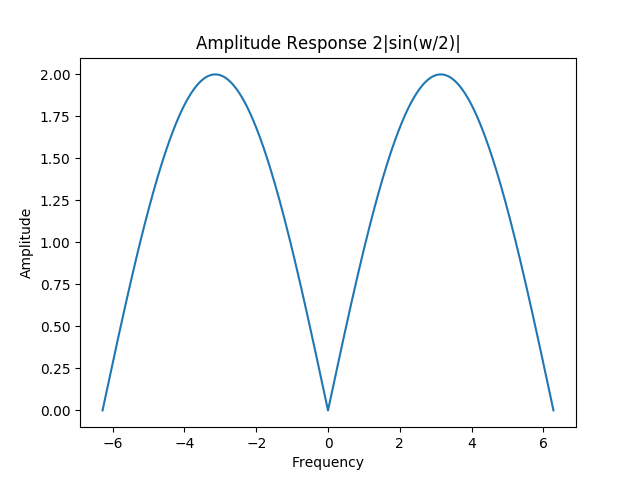

The difficulty arises when we introduce higher frequency noise. The z-transform of the transfer function is $ H(z) = \frac{1 - Z^{-1}}{T} $ so the frequency response is $ H(e^{j\omega}) = \frac{1 - e^{-j\omega}}{T}$. Taking the magnitude gives the amplitude response. It is kind of weird.

A key feature is that amplitude shrinks to zero for $\omega = 0$. This makes sense since the derivative of a constant signal should be zero. However, this also makes our system act like a high pass filter. It amplifies our higher frequency noise relative to the lower frequency signal.

There are many approaches to solve this issue, but we are looking for one that is simple to implement, fast, and has minimal phase lag. These properties are important since we use signals and their derivatives to make torque vectoring decisions. If the results are too laggy, then our torque vectoring controller won’t be responsive.

I found a paper Realtime Implementation of an Algebraic Derivative Estimation Scheme by Josef Zehetner, Johann Reger, and Martin Horn with a highly satisfactory method. I would recommend you read their paper for the full details. Essentially, we isolate a particular term in the Taylor series of the signal by applying a linear operator to a series ‘window’ of recent values. This method is nice since it only requires maintaining a circular buffer of the most recent samples. When we want to read the filter, we only need to sum a poylnomial function over each value in this window.

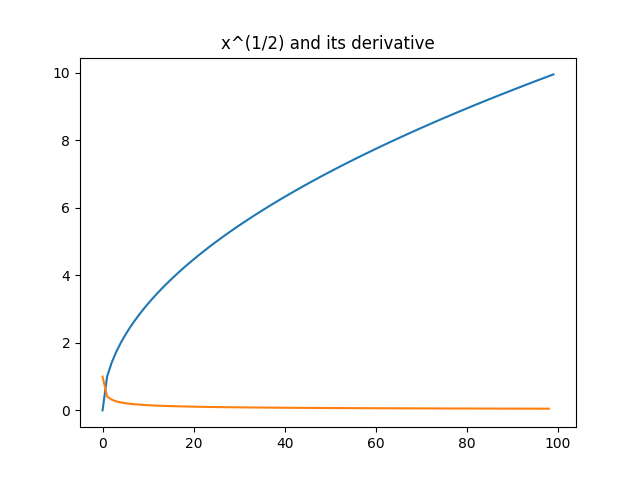

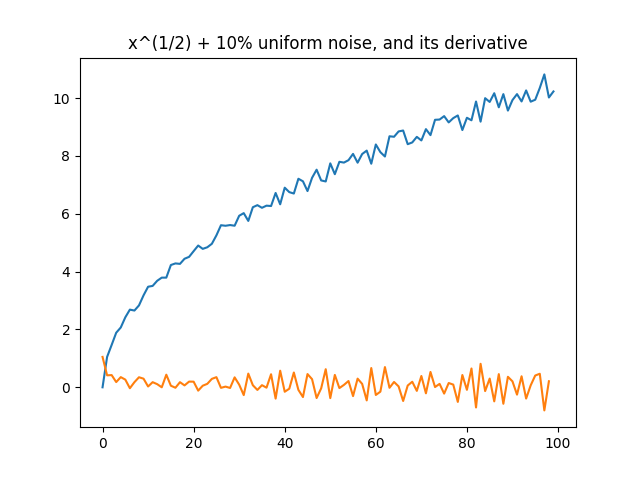

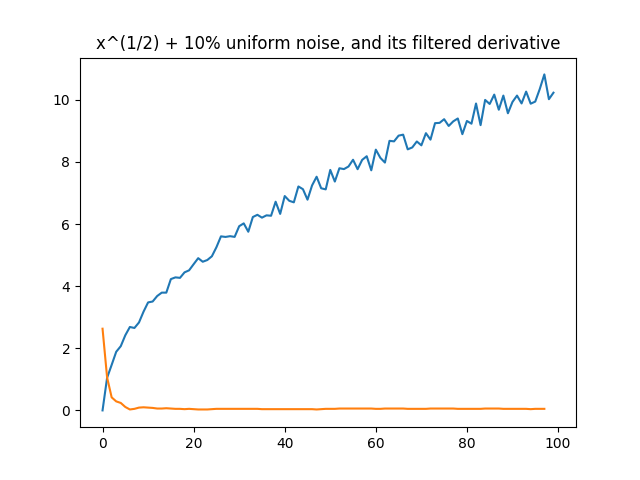

It works pretty good. Here is an example with $x[n] = \sqrt{n}$

Without any noise, our basic sequential difference method works well.

But once we add noise, it falls apart. You may notice that there is actually more noise in the derivative than the original signal.

Our derivative filter comes to the rescue though. Other than some weirdness caused by the shortened window near the begining of the signal, it looks pretty good.

Just since they are real sweet, I might add some more plots of piecewise signals later. If you’d like to see the code for the filter you can find it here.